Watercolor

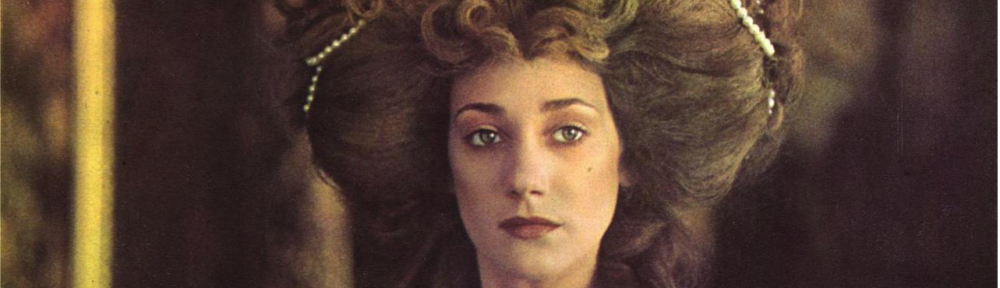

In a recent post, a film blogger took issue with the performance of Marisa Berenson as Lady Honoria Lyndon in Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 film Barry Lyndon. He opined that Berenson was stiff and lifeless and Kubrick should never have put up with such a performance from her but should have brought in another actor.

In a recent post, a film blogger took issue with the performance of Marisa Berenson as Lady Honoria Lyndon in Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 film Barry Lyndon. He opined that Berenson was stiff and lifeless and Kubrick should never have put up with such a performance from her but should have brought in another actor.

In reality, of course, Berenson was giving exactly the performance that Stanley wanted. She is the ideal to which Barry aspired. Once he attained it, he finds that she, and his dream of wealth and power, are lacking. Barry has nothing like the earnest feelings he once had for his cousin back in Ireland. And, indeed, chasing his goal has left its mark on Barry, he is ultimately nearly as hollow as Lady Lyndon herself. His last authentic feelings are for his son Bryan and those are drained when the boy dies as the result of a riding accident.

Perhaps the one element of the story that doesn’t ring true is Barry’s final noble gesture of firing into the ground during his duel with Lord Bullingdon (superbly played by the late Leon Vitali). If Kubrick had stuck to his guns in showing a world where the true cost of climbing the ladder is complete moral decay (no matter how Thackeray plotted the original novel), he would have had Barry put his pistol shot through Bullingdon’s eye. Barry would have his success ratified, with no more young Bullingdon to challenge him for the estate. He would have complete victory but with the corpses of his son and Bullingdon as the companions of his triumph. The coldest possible end to Thackeray’s story.

The human penchant for seeing patterns is legendary. Recall the “human face on Mars.” For decades it was splashed across the covers of check-out line tabloids. When the Mars Global Surveyor spacecraft arrived at Mars in the late 1990s with a much higher resolution camera than that carried by the Viking I mission in 1976 it was obvious that there was no face at all. Just human brains and reflexive pattern recognition. We can’t stop ourselves.

A much higher resolution image from the Mars Global Surveyor shows that the “face” is just another Martian hill.

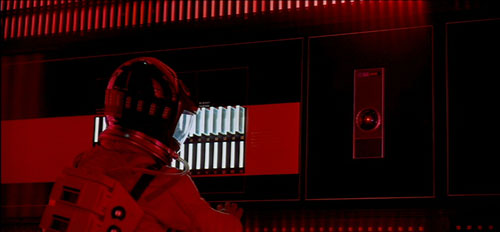

This poetry in patterns is the delight of art lovers and conspiracy theorists alike. Not to mention the analysts of cinema on YouTube. During a recent drift through YouTube, I watched a video commenting on Stanley Kubrick’s 2001. The video claimed that any object in the film that was remotely oblong was there to invoke the film’s famous black monolith. And that Stanley had obsessively planned this down to every last angle to underscore the importance of the monolith. The more prosaic explanation is that a rectangle is kinda the natural shape for lots of things and Stanley had a film to finish.

There was one interesting set of rectangles in the film, however, that I had never seen that way before. It’s when David Bowman (Keir Dullea) releases the memory elements of the HAL 9000 ship’s computer. And as he does so a family of monoliths rise one at a time to take their places in a tableau vivant. The sequence is visually striking, like all of 2001, and it’s emotionally wrenching too. Poor HAL’s memory is going and he can feel it. And we can’t help feel a little sad as well. HAL is a smug prick of a computer, but he does run a tight ship and he exhibits more piss and vinegar in the film than Bowman or his fellow astronaut Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood).

There was one interesting set of rectangles in the film, however, that I had never seen that way before. It’s when David Bowman (Keir Dullea) releases the memory elements of the HAL 9000 ship’s computer. And as he does so a family of monoliths rise one at a time to take their places in a tableau vivant. The sequence is visually striking, like all of 2001, and it’s emotionally wrenching too. Poor HAL’s memory is going and he can feel it. And we can’t help feel a little sad as well. HAL is a smug prick of a computer, but he does run a tight ship and he exhibits more piss and vinegar in the film than Bowman or his fellow astronaut Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood).

With his pride, paranoia and murderous disdain for his fellow crewmembers, HAL is actually the most human character on board the good spaceship Discovery One. Tightly wrapped Bowman and Poole are more akin to lifeless silicon simulations than the marvelously nutso HAL. They’re the robots. They were made to be so by the relentlessly scientific industrialization of modern society — as a popular meme from the late 60s would have it. That we would all become sons and daughters of the computer. Back then, of course, no one foresaw that instead of turning humans all into cold, calculating automatons the future would instead gift us TicToc, Twitter and YouTube, reducing humanity to emotional scrollers intent on sensation with rarely a thought to science.

Anyway, when Bowman does zotz HAL’s memory and force the poor 9000 to devolve into a mindless machine that maintains the ship’s systems, Bowman regains a measure of his humanity. HAL, that epitome of restrictive scientism, is no longer Bowman’s jailer. He’s a free man, able to act on his impulses. So he can’t resist following his curiosity. He climbs into a pod — opening the pod bay doors himself, thank you very much — and flies off to the Stargate and his rendezvous with destiny in the green room where he will go from human to Star child.

What to get your dad for his birthday? An annual problem for offspring everywhere. While I no longer face this vexing question — my dad passed in 2009 — my three sons still deal with the challenge. This year my youngest had a novel answer. Knowing my interest in sketching, he purchased a “visual journal” for me.

What to get your dad for his birthday? An annual problem for offspring everywhere. While I no longer face this vexing question — my dad passed in 2009 — my three sons still deal with the challenge. This year my youngest had a novel answer. Knowing my interest in sketching, he purchased a “visual journal” for me.

There’s a space for a drawing each day for a year. 365 daily drawings. Great idea. Thoughtful and fun.

Although, I have to say, it has raised some new vexing questions. After a good start I’m already falling behind a bit. So I wonder: Is it cheating to do three drawings and backdate two of them? Or must the drawing be done on the date stated? What is ethical when it comes to sketching? Is there a higher law — an immutable code of conduct when pencil meets paper? Damn, I just wanted to make a little sketch, not grapple with morality.

Harold was hasty to Hastings

But now billets at Bosham,

Traveling no more

From the West Sussex shore.*

*Today is the 956-year anniversary of the day William I (the Conqueror) and his gang of Norman toughs landed on the southern English coast at Pevensey. Only three days before, on September 25th, the English king (really the Anglo-Saxon king) Harold Godwinson (one of the few kings to be referred to by his first and last names) had defeated a Viking army at the battle of Stamford Bridge in northern England. But he had no time for victory parades, mead hall bacchanals or fist-pumping appearances on the Tonight Show. Harold had to haul ass south to confront the annoyingly confident William (who reportedly said to his henchmen when stepping ashore and grabbing some pebbles from the beach: “See, I have England in my hands. It is now mine and what is mine will be yours.”). Harold did confront Billy at the Battle of Hastings on Oct. 14, 1066. But Godwinson lost the fight, the throne and his life. The exact whereabouts of Harold’s grave are not precisely known, but are generally accepted to be in Bosham Church in West Sussex not far from the port city of Portsmouth.

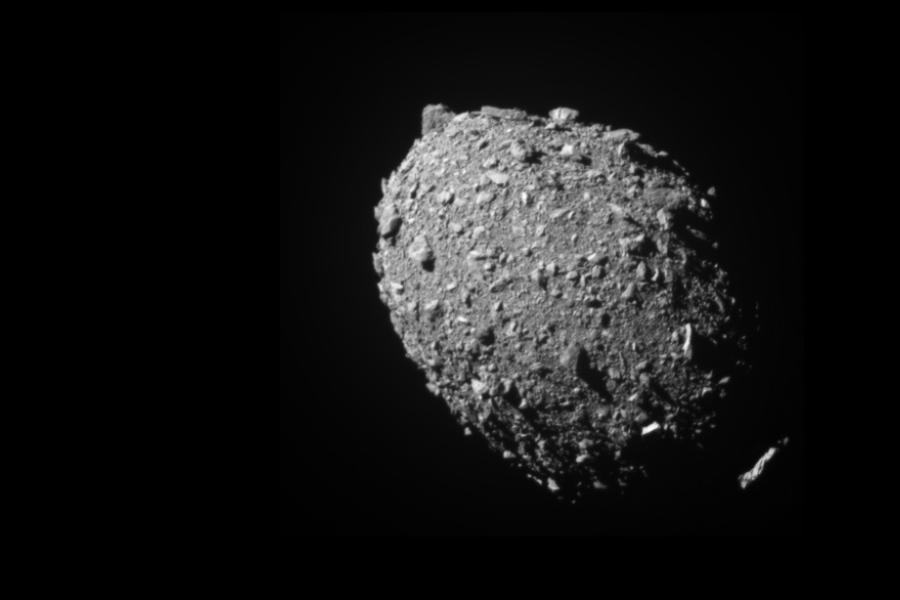

NASA’s plucky DART spacecraft was sent to do nasty things to the tiny asteroid moonlet Dimorphos. It accomplished its mission yesterday, Sept. 26, 2022. The big event was part of research into planetary defense — the effort to find a way to prevent a future earth-hunting asteroid from ruining our collective day by impacting the planet and throwing several hundred million tons of vaporized dirt, rock and humans into the atmosphere.

Throughout the approach and aftermath of DART’s attack on Dimorphos, NASA scientists and media commentators rightly lauded the high-tech effort and all the planning and precision that went into it.

But what about the actual attack on Dimorphos? Was that done using some kinda’ high-tech energy weapon recently developed in a lab? Some “pew-pewing” Star Wars laser?

Nope. This attack was no more sophisticated than the stone cannon balls blasted at the walls of Constantinople in 1453 from the siege guns of the Turks who really wanted in. No more sophisticated than the iron cannon balls fired by the English at the lumbering ships of the Spanish Armada in 1588.

DART smashed into Dimorphos using a technique brought to us by centuries of gunpowder: the simple collision of a solid projectile hitting the broad side of a barn. Boom.

Who needs fancy “pew pewing” when you’ve got classical physics? Sit down Albert and Herr Heisenberg, Sir Isaac says, “I got this.”

In late January 1862, a strange fleet of ships sank en masse off Charleston Harbor. One of these, a barque named Margaret Scott, was completing an ironic circle of fate. A former whaler seized as a slave ship, the barque was part of an effort to stop Confederate blockade runners — like the convicted pirate Appleton Oaksmith, the very man who first set Scott on its fateful course to the bottom of the Charleston ship channel.

In late January 1862, a strange fleet of ships sank en masse off Charleston Harbor. One of these, a barque named Margaret Scott, was completing an ironic circle of fate. A former whaler seized as a slave ship, the barque was part of an effort to stop Confederate blockade runners — like the convicted pirate Appleton Oaksmith, the very man who first set Scott on its fateful course to the bottom of the Charleston ship channel.

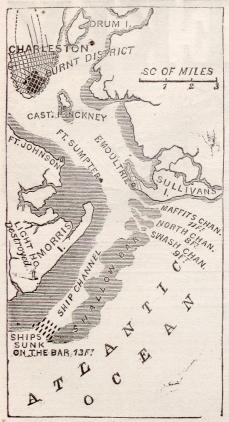

The ships that sank 160 years ago were dubbed the “Great Stone Fleet.” A collection of former whaling ships purchased by the U.S. government, they were assembled by the navy for a peculiar duty: to be filled with a cargo of stone, sailed south and then sunk at the entrance of South Carolina’s major port. The plan was to make two of Charleston’s three main channels unnavigable, funneling blockade runners toward the U.S. naval squadron on blockade duty.

The 46 ships were sunk in two groups — one in December 1861 in the main channel and a second group in January 1862 in Mafitt’s channel to the northeast, off Sullivan’s island. Each vessel, depending on its capacity, it had been loaded with between 190 and 550 tons of stone. Holes had been bored in each hull and then stoppered with large plugs. Once the ships were anchored in position, men were sent aboard with axes and sledgehammers. These wrecking crews first chopped away the ship’s rigging. An account from the January 11, 1862 Harpers Weekly details the destruction: “The braces and shrouds on the weather side were cut by the sharp axes of the whalemen, and the tall masts, swaying for an instant, fell together with a loud crash, the sticks snapping like brittle pipe-stems close to the deck, and striking the water like an avalanche, beating it into a foam and throwing the spray high into the air.”

After the masts fell, a select group clambered belowdecks with the heavy hammers to knock the plugs free and allow the waters of the Atlantic to firehose through the bore holes.

Margaret Scott was one of 20 vessels sunk off Sullivan’s Island. Like most of the stone fleet, Margaret Scott was once a whaler. The vessel was named after one of the innocent women executed in Salem, Massachusetts, during the 1692 witch trial hysteria. For the owners of Margaret Scott, the whaling business had fallen on hard times, with many small whaling enterprises closing down and idling ships in whaling ports like New Bedford.

To a small group of maritime criminals, these vessels, which could be purchased at depressed prices, were an opportunity. These former whalers were snatched up for a vile game of bait and switch. Still outfitted with whaling gear, although mostly played out from long use, these ships maintained the pretense of whaling, but in fact their new masters used them as slave ships.

Though the transatlantic slave trade was outlawed in the United States and Britain by laws in 1807 and 1820, and by 1831 in the Spanish colonies and Brazil, illegal shipments of enslaved Africans continued.

In New York City and in small harbors on Long Island like Oyster Bay and Greenport, slave ships were outfitted in the late 1850s and up to the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861. The buyer of Margaret Scott was a shady operator named Appleton Oaksmith. The proprietor of a small ship brokerage firm, Oaksmith had purchased other vessels for the slave trade. As in his previous dealings, Oaksmith was careful to use former whaling captains Ambrose Landre and Samuel P. Skinner as intermediaries to obscure his involvement in purchasing Margaret Scott. Oaksmith paid $2,400 for the vessel, a good deal less than the going rate.

With the assistance of Landre and Skinner — the latter named as the titular owner of the barque to maintain the ruse — Oaksmith outfitted Margaret Smith for the ship’s horrifying new role. In these former whalers, bulkheads in the hold were rebuilt to better contain the loading of humans rather than barrels of whale oil. Extra water tanks were also added. Whale ships with tryworks for boiling down whale blubber for oil were repurposed to cook food for the hundreds of slaves.

Customs officers and port officials noted the changes made to these former whale ships and suspected that they were being outfitted as slave ships. In the 1850s, however, during the administration of President Buchanan, enforcement was lax. There were few Federal funds for going after these suspected criminals and the fake whalers often sailed without any hindrance. Sometimes these ships would maintain the charade of whaling by going to whaling grounds off West Africa and even taking a whale. The crews were hired as whalers and were generally well paid. Margaret Scott crewman were promised $500 for the voyage by Oaksmith, Landre and Skinner. These sailors were regularly not told the truth of the voyage before departure. When they were informed, often in African waters, they usually acquiesced. Hard-pressed sailors were unlikely to forfeit the wages offered. According to “Slavers in Disguise: American Whaling and the African Slave Trade 1845-1862” by Kevin S. Reilly, published in The American Neptunemagazine, Oaksmith reportedly told Landre, “…it would not do for anyone, officers or men, to know the ship was going to the coast of Africa. Mr. Oaksmith said everything would be made right when we came there to the coast. They [the crew] would all come into it, they always did.”

Things changed after the 1860 election and the arrival of the Lincoln administration. After the southern states seceded and their members of Congress were no longer on hand to block antislavery legislation, funds were appropriated to suppress these slave ships. Some port officials were ready for the change. And they had Oaksmith in their sights. As quoted by Reilly, one port inspector wrote to his superior: “I know Appley, Oaksmith, Israel Peck, and Captain Isaac M. Cas[e] very well. I know their views with regard to secession and slavery, especially the African slave trade…. [T]hey are a damnable set, the whole of them.”

Before Margaret Scott could sail, though, the federal marshall in New Bedford swooped in and seized the vessel. He also arrested Oaksmith, Landre and Skinner as pirates under the 1820 law that made participation in the slave trade an act of piracy. Tried in Massachusetts District court in 1862, Skinner was prosecuted by antislavery district attorney Richard Henry Dana, Jr. (who as a young man had written Two Years Before the Mast, a famous account of his time as a seaman aboard the merchant brig Pilgrim). Skinner was convicted, receiving a five-year prison sentence and a $1,000 fine. It was the first time an American ship captain had been convicted as pirate for planning and preparing a slaving voyage.

Similarly tried and found guilty, Oaksmith pulled off an escape from the Suffolk County jail before he was sentenced for his eight-count conviction. It’s not hard to imagine the shady criminal’s escape was augmented by some well-placed bribes. He fled to the south and used his maritime knowledge to become a blockade runner for the Confederacy.

After Margaret Scott’s seizure in New Bedford, the whaler turned slave ship was added to the other whalers of the great stone fleet and sent to the bottom off Charleston. A poetic end to the story of the whaling barque would have blockade runner Appleton Oaksmith fleeing Union ships before getting snagged by the very ship that earned his conviction as a pirate. History doesn’t give us this satisfaction, however. Oaksmith ceased his blockade running and bought a plantation in New Bern, North Carolina. Ever the criminal operator, after the war he obtained an audience with President Grant at the White House and finagled a presidential pardon for his slaving conviction.

Margaret Scott’s final voyage to make a bar to blockade runners wasn’t ultimately a success. Within a year the tides and currents broke up and scattered the stone fleet wrecks, and the bottom sands shifted to create new channels. By 1863, however, the Union Navy was well into its wartime expansion and many new ships were available for the blockading squadrons off southern ports.

Sources:

Magune, Frank; “The Great Stone Fleet,” pgs. 106 – 113; Yankees Under Sail, Yankee Inc. 1968

Harper’s Weekly, pg 31, January 11, 1862.

Reilly, Kevin S.; “Slavers in Disguise: American Whaling and the African Slave Trade 1845-1862,” pgs. 177 – 189; The American Neptune, 1993

Marques, Leonardo; “The Contraband Slave Trade to Brazil and the Dynamics of US Participation 1831 – 1856,” pgs. 659 – 684; Journal of Latin American Studies vol. 47, 2015

In the 1987 film Wall Street the odious financier Gordon Gekko baldly proclaims, “Greed is good.” This New Years 2022, the German government has updated Gekko’s missive to “Global Warming is Good.”

As of January 2022 the Germans are completing their plan to shut down six low-carbon nuclear power plants. Facilities that are superbly run, indeed, are acknowledged as among the best in the world. Each of them could operate for decades more. They provide 8.4 gigawatts of power to the German grid and produce virtually no CO2. But they are being shut down for purely ideological reasons. “Nuclear power is bad, we don’t care about global warming” is the depth of the policy from the German Green Party and the German government.

And what will replace the power from these plants? High carbon emissions from German coal plants. These are particularly bad because many of them burn lignite or brown coal, which is a worse polluter than standard hard coal. And the Germans strip mine this lignite so voraciously that whole towns have been wiped off the map to get at it.

Maybe the coal plants should be turned off too. According to the German government they will be, but not for another ten years or so!

So the plan is to shut down the non-carbon producing plants now but let the carbon monsters keep spewing their emissions for another decade.

It’s Germany’s tip of the hat to Mr. Gekko.

While everyone these days makes a “making of” video, the ancient Egyptians decided to let their work speak for itself. They never tossed a video on YouTube explaining how they built the pyramids. So while there are a variety of theories about how they piled up all those stone blocks, even the most obsessed of Egyptologists don’t really know the answer.

Was it massive ramps, lifting cranes, elevators (yes, that has been suggested)? Ramps are a problem because to build a ramp or ramps to reach the top of the Great Pyramid would require as much or more work as it took to build the pyramids themselves. Lifting cranes are a possibility, but they require some heavy-duty wood to lift the multi-ton stone blocks (the Egyptians didn’t have wood of this quality and would need to import from a place like Lebanon). And the idea of wooden elevators inside the pyramid seems a little far fetched.

But there’s a German fellow named Franz Lohner who has a different theory on how the Great Pyramid was constructed. A former worker in a quarry, Lohner’s idea is that the builders made use of the sloped sides of the pyramid as their “ramp.”

According to Lohner, the Egyptians built a wooden track that was secured to the side of the pyramid. This track was used to lift the stones, which were lashed to wooden sledges. The tracks were lubricated with an oil and water mixture.

The true genius of Lohner’s idea, however, rests with the use of a primitive type of turning block that could change the direction of a lifting rope 180°. He calls these turning blocks “rope rolls.” The rope is led up through two rope rolls, one on either side of the track, and then back down the track to where two teams of workers make use of their own weight to head down the track, pulling the stone up. A clever idea that is far less expensive and time consuming than building massive ramps.

Even though the Egyptians didn’t have the wheel or pulleys, Lohner contends that inside one of the major pyramids there is an example of a log used to change the direction of ropes in this way. So the concept was likely not foreign to the clever engineers who built these massive structures.

Check out his site, which contains drawings and detailed explanations of his ideas. For pyramid fans, its well worth the visit. Who knows, maybe Lohner has cracked the case.